The majority of allied health professionals in residential elderly care are physiotherapists, making around 21% of the workforce. Unfortunately, a lot of the work done with elderly patients is, in my opinion, woeful. The focus for those advanced in years should not be walking, cycling, swimming and other forms of endurance exercise. And God forbid options like yoga, tai chi and stretching (or any other chronically underloaded exercise) takes priority. If I had to choose one mode of exercise to benefit the elderly, it would undoubtedly be heavy resistance training. The rest of this blog post will be my justification of this choice.

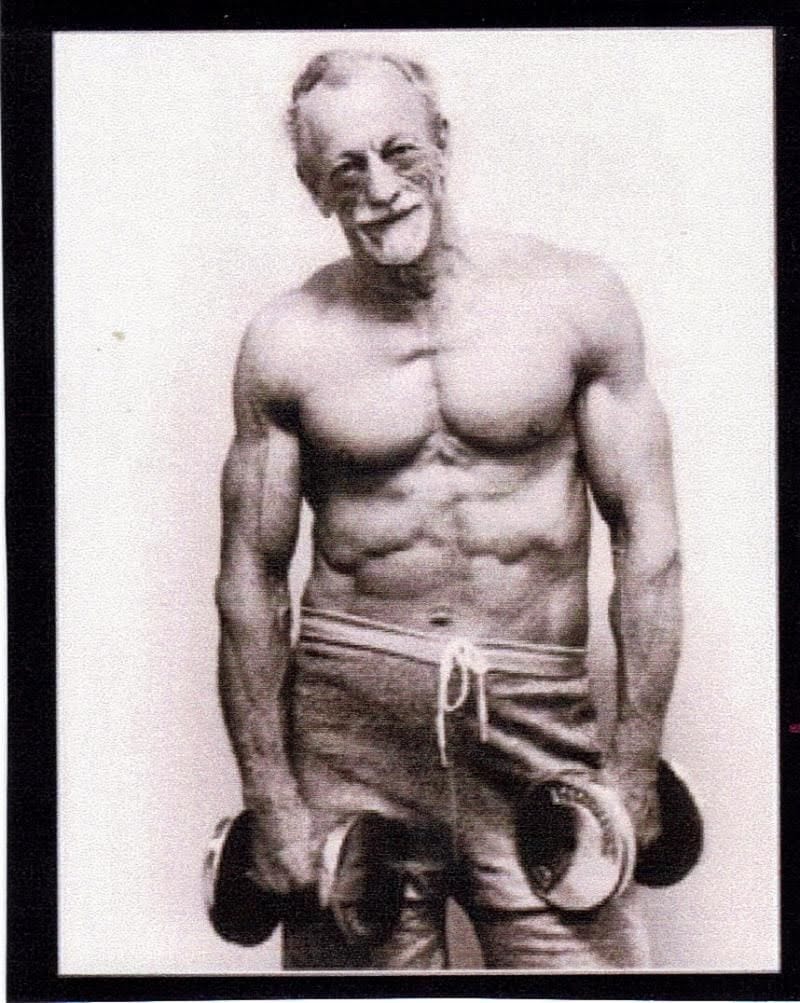

This picture depicts a man in his 50s or 60s executing a deadlift with a weight of 240kg. I speculate that less than 2% of men in their 20s have the capacity to lift such a heavy load, and all of them would need to be engaged in regular strength training. It’s clear that middle age doesn’t necessarily equate to having a bulging waistline and frail sarcopenic limbs.

Resistance training staves off sarcopaenia

Sarcopenia was a term originally used to described the age-related loss of skeletal muscle. The term is now used to describe all the age-related changes in skeletal muscle including the neural control that innervates it. Why is sarcopaenia bad? Well, it significantly reduces quality of life, reduces your ability to perform basic activities of daily living and if it remains unaddressed will progress to the point someone needs full time care. It is significantly associated with death from any cause.

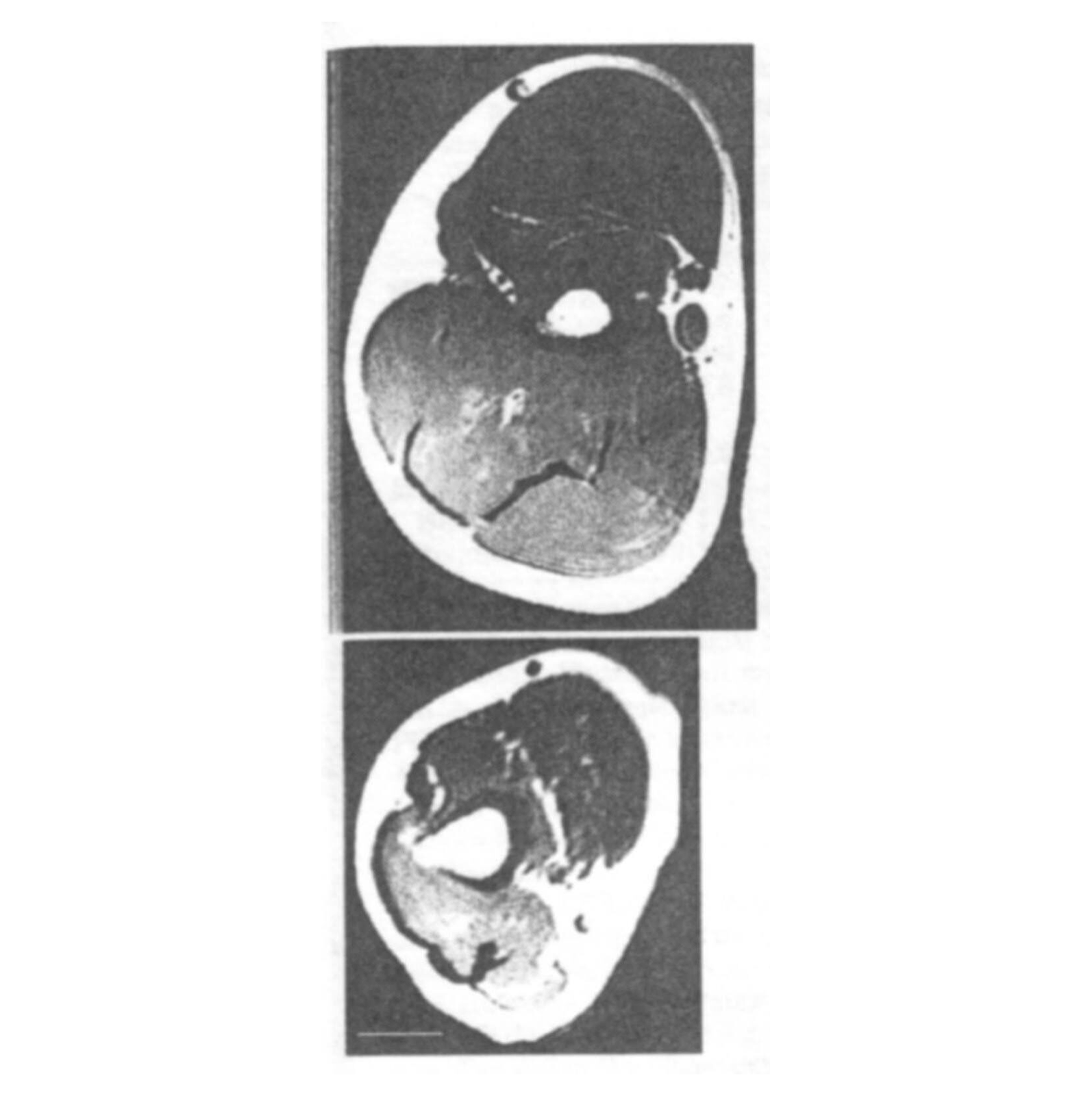

Note the marked decline in muscle mass with ageing in the image (bottom image; a 95yo, top image; a 22yo) (Klein, 2001). This is an image of the triceps brachii (a muscle that straightens the arm) which is particularly wasted in the older man, presumably because it’s utilised significantly less than the elbow flexors during activities of daily living. Clearly push-ups and bench presses were not a part of this older gentleman’s lifestyle. If you want to nerd out, read on. Otherwise, skip to the picture of the jacked old dude holding dumbbells for my quick take-away.

What specific changes are associated with sarcopaenia?

1. Decreased muscle fibre cross-sectional area

- 25-50% vs 1-25% reductions in fast twitch (FT) vs slow twitch (ST) fibre CSAs

Muscle atrophy (loss of skeletal muscle size) is a major contributor to the age-related decline in strength. It has been reported that the FT fibres (type IIa and IIb) atrophy significantly more than ST fibres (type I), but why? Presumably because most humans are, sadly, sedentary and rarely recruit larger motor units.

2. Loss of motor units and fibres (mostly type II)

- Due to motor neuron (MN) death!

- Results in fewer, larger fibres due to reinnervation

Motor unit loss also occurs with ageing as a consequence of MN death. When MN’s die they obviously leave their muscle fibres deinnervated (no nerve connection). These fibres atrophy rapidly. Occasionally, some of them are reinnervated by surviving MN’s and effectively ‘adopted’ into the surviving motor unit. Surviving motor neurones seem to ‘know’ to send out axon branches to fuse with deinnervated muscle fibres and form new neuromuscular junctions! Because type II MN’s are more prone to ‘cell death’ than type I MN’s, the reinnervation process converts fast fibres into slower ones. This results in a significant increase in the size of type I units and a reduction in the number of motor units within the muscle.

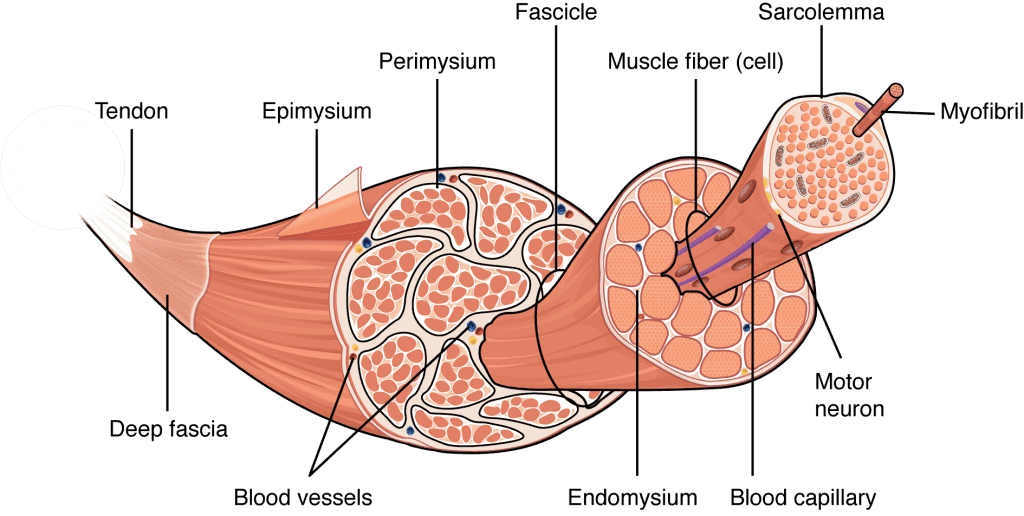

3. Decreased fascicle length

Fascicles are the tiny tubes of contracting tissue which form bundles together, eventually becoming a muscle fibre. Fascicle lengths have been shown to decline with age and this appears to explain some of the decline in maximal muscle contraction velocity and power with age. Boo!

4. Increased intramuscular fat and connective tissue

The muscles of elderly people have a greater content of intramuscular fat and connective tissue. As these make no contribution to active force generation, they contribute to a reduction in strength per unit of PCSA. They’re essentially just dead weight!

5. Increased muscle co-activation

There is mixed evidence as to whether or not the elderly lose strength as a consequence of reduced capacities to activate their muscles. Some studies show no decline in this parameter while others do. Perhaps the disparate results reflect differences in the frailty of the subjects chosen in each of the studies?

6. Reduced motor control, proprioception and balance

- This increases falls risk and reduces the steadiness of muscle force (fine motor control; think doing up buttons, using a smartphone etc.)

The bottom line? These age-related changes in muscles and cannot be meaningfully reversed or reduced with endurance exercises!

The elderly are more likely to trip, have a reduced capacity to sense imbalance and have a reduced capacity to rapidly correct imbalance. Fall risk increases simultaneously with reduced bone mineral density and therefore also increases fracture risk. The control of the motor system declines with age. Changes in the vestibular apparatus and to proprioception create problems sensing losses of equilibrium (balance) while the reduction in muscle power reduces one’s ability to make the relatively rapid corrections that are necessary to stay upright. Falling on osteoporotic bones is clearly a fracture hazard and hip fractures greatly increase risk of all-cause mortality.

If you’ve just skipped here, the take-away is that the elderly have smaller, slower, weaker, shorter, clumsier and less-efficient muscles.

Why do resistance training?

Loss of strength and power has a large impact on activities of daily living. Unfortunately, endurance exercises (prolonged walking, jogging, swimming etc.) are often performed instead of heavy resistance training. I hope by now you see this is a huge mistake! Other forms of exercise do not prevent muscle wasting. Resistance training can increase functional capacity, even in the very old. If you only do one type of exercise after the age of 60 it should almost certainly be resistance training! Of course doing a broader spectrum of activities would be better for your health. And of course it’s important to find exercise and activity one enjoys. But the evidence is clear; if you had to make a choice of one single type of training, it should be lifting heavy things.

Your endurance or aerobic power is of little use if you are no longer strong enough to get out of a chair!

Furthermore, studies on masters athletes in a range of sports reveal that running, cycling and swimming have little to no effect on sarcopenia with advancing age. Lastly, there is a wealth of evidence that functional capacity can be improved, even in 90+ year olds, as a consequence of resistance training.

Here are a few reasons to prioritise strength training:

- Increase power

- Increase endurance

- Decrease insulin resistance

- Reduce total & intra-abdominal fat

- Increase resting metabolic rate in men

- Reduce the loss of BMD with age (reducing fracture risk)

- Reduce fall risk factors

- Reduce pain in osteoarthritis of the knee (more info here, here, and here)

- Reduce incidence of psychosocial issues (depression, anxiety etc.), even more so than GP care

- There’s an increased incidence of depression with old age (perhaps due to loss of independence, socialising and physical capacity?)

- There’s an increased incidence of depression with old age (perhaps due to loss of independence, socialising and physical capacity?)

Skeletal muscle is really forgiving. We can neglect it for 40-70 years of adulthood and it still responds positively to a training stimulus. Furthermore, it remains so adaptable that 2-3 months of resistance training can reverse 20 years worth of decline! Unfortunately other tissues, such as bone, are not so forgiving. These require more constant attention across the life-span.

The elderly are, despite the common misconception of youth, not another species!

Resistance training guidelines for young people are very much applicable to the elderly. Many healthy and relatively fit elderly people will not require programs that differ significantly from those for 20-40 year olds. For the frail elderly (those with signs of sarcopenia), however, a more specific program that prioritises activities of daily living seems appropriate. The use of a step-up, for example, would have a more direct transfer to stair walking than would the leg press or even a squat.

Of course this doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t squat (or leg press), in fact a combination of the two might maximise both hypertrophy and functional benefits. To enhance gait you should also consider that the knee extensors (quadriceps) and plantar flexors (calves) deteriorate faster with age than the hip extensors, so squats and leg presses should be performed in manner that maximises quadriceps activity (e.g. high bar for squats; feet low on the foot plate with the back rest declined for leg press). Moreover, a calf exercise seems appropriate and is probably of more value than a leg curl or back extension.

Blood pressure considerations

Importantly, your blood pressure (BP) may need to be considered. Minimising high BP may be necessary as a relatively high percentage of people in the 60+ age bracket have elevated resting BP and some arterial stiffness. You can minimise high BP by:

- incorporating unilateral rather than bilateral exercises (particularly for the legs),

- pausing briefly between repetitions,

- performing sets with fewer repetitions,

- as BP seems to accumulate with each rep, 1) BP would be higher after a high rep set and 2) BP would be elevated for a longer time as it takes longer to complete the high-rep set,

- fascinatingly, this may mean a heavier weight should be used for fewer reps,

- as BP seems to accumulate with each rep, 1) BP would be higher after a high rep set and 2) BP would be elevated for a longer time as it takes longer to complete the high-rep set,

- stopping sets 1-3 reps prior to failure (particularly when training for power),

- and performing eccentrically biased exercises that involve lifting a load with 2 limbs and lowering it with one.

Options for exercise selection

- Squats

- DB deadlifts, lunges, step-ups, vertical jumps

- Bench press

- push-ups, medicine ball push-pass

- DB row

- cable rows, lat pulldowns

- DB calf raise

- unilateral or bilateral

- Crunch

- side crunch, prone and side bridges

Here are some examples of the sorts of exercises that could be used in the resistance programs of the young and the elderly. None of them are mandatory and this isn’t an exhaustive list; there are obviously plenty of great exercises that aren’t included. The way I like to educate patients is to say that we’re cooking (throwing sensible ingredients together and seeing what works) not baking (following a rigid recipe).

Jean, 82yo, with a new PR of 153kgs for the deadlift! One of my favourite pictures on the internet!

For the lower limb, the emphasis should be on anti-gravity muscles – think, quadriceps and calves. Moreover, a lot of these exercises will require some measure of balance. Some of you will be apprehensive about performing jumping activities (and it should be acknowledged that the very frail will not be able to leave earth). If this is you, simply performing the concentric part of the exercise as fast as you can will suffice. But if you can still jump safely (even if it just a few centimetres), you should! Use it or lose it.

The DB squat involves holding a single DB (by the plates at one end) between the legs. This is a good functional alternative to traditional barbell back squats as it avoids the discomfort associated with placing a heavy load across the shoulders while providing a model of how to safely lift items around the house. This and the traditional squat can be modified to include plantar-flexion at the end of the movement. Push-ups can be performed with the hands on a table or kitchen bench so they need not be too difficult even for the frail. The idea behind the use of body mass exercises is that they are more specific to activities of daily living – the push-up may be a component of getting up off the ground after a fall. Abdominal exercises should include those that tax the flexors and lateral flexors with the view to maintaining the ability to roll and sit up (an important pre-requisite to getting up off the ground or out of bed – in this sense the act of getting up from the ground will act as a positive training stimulus for some frailer folk).

Many of these exercises place significant compressive loads on bones that are prone to osteoporotic fractures such as the vertebral column, neck of the femur, the carpals, radius and humerus. You should recognise, however, that those who already have severe osteoporosis may come to harm if these sites are loaded excessively. Arthritic changes, common in the joints of the elderly, may limit exercise choice or the range of motion (ROM) that older lifters can move through. Modifying the ROM should be seen as preferable to abandoning the exercise completely.

Dietary considerations

- Meal timing

- Some evidence exists for timing protein with RT to increase the degree of hypertrophy (the evidence is not conclusive here however, and perhaps it’s best to simply recommend training in a “well-fed” state and ensure appropriate hydration).

- General concerns

- There are contradictory opinions regarding protein requirements in the elderly

- Some suggest that the elderly may have increased protein requirements, although this is not universally agreed upon. One potential detrimental effect of aging on muscle growth is the decline in appetite (the anorexia of aging) that occurs.

- Appetite declines with age

- The elderly often have other comorbidities that may necessitate alterations in diet (e.g., reduced kidney function)

- There are contradictory opinions regarding protein requirements in the elderly

The best time to consume protein is immediately before and immediately after resistance training. There are some studies that show even greater benefits for the elderly. Esmark and colleagues reported that taking a protein-carbohydrate supplement immediately after training resulted in significantly greater increases in muscle fibre cross-section than taking the same supplement 2 hours after training. This suggests that there may be a narrow “window of opportunity” for the elderly who should be encouraged to eat appropriately soon after, or even before ‘working out’ (though new evidence has challenged this, suggesting it’s more of a “barn door” than a “narrow window”).

Thanks for reading!

For thorough assessment and treatment book in! We’d love to help you navigate your low back pain!